“Achievement of business performance by the partent company through bullying suppliers is totally alien to the spirit of the Toyota Production System.”

Taiichi Ohno

A Part is Not a Part, and A Supplier is Not a Supplier

When customers buy cars, they do not care who makes the engine, radio, seat, carpet, etc. they want and expect reliable quality and hold the automaker totally accountable for anything that is not up to their expectations. Toyota recognizes this and makes sure that every car part reflects Toyota quality. To achieve this and makes sure that every car part reflects Toyota’s PD process and lean logistics chain.

Other companies largely failed in emulating the Toyota model because they have not grasped the concept of true partnering. When the market gets though and there are serious earnings pressures, they have been less than forthright with suppliers, vacillating between public statements of commitment to partnership and trust and then unilaterally cutting supplier prices after signing contracts. They have even cut off suppliers in the middle of contract, resourcing it to a lower bidder. Toyota (as the supplier’s most demanding customer) to the contrary works on improving the supplier’s efficiency. For example when Toyota noticing that they were paying suppliers for many key parts above the lowest prices competitors paid globally, it issued a new target for all key suppliers as part of a program. The new program asked suppliers to reduce prices by 30 percent for the next model line; typically this would over a period of about three years.

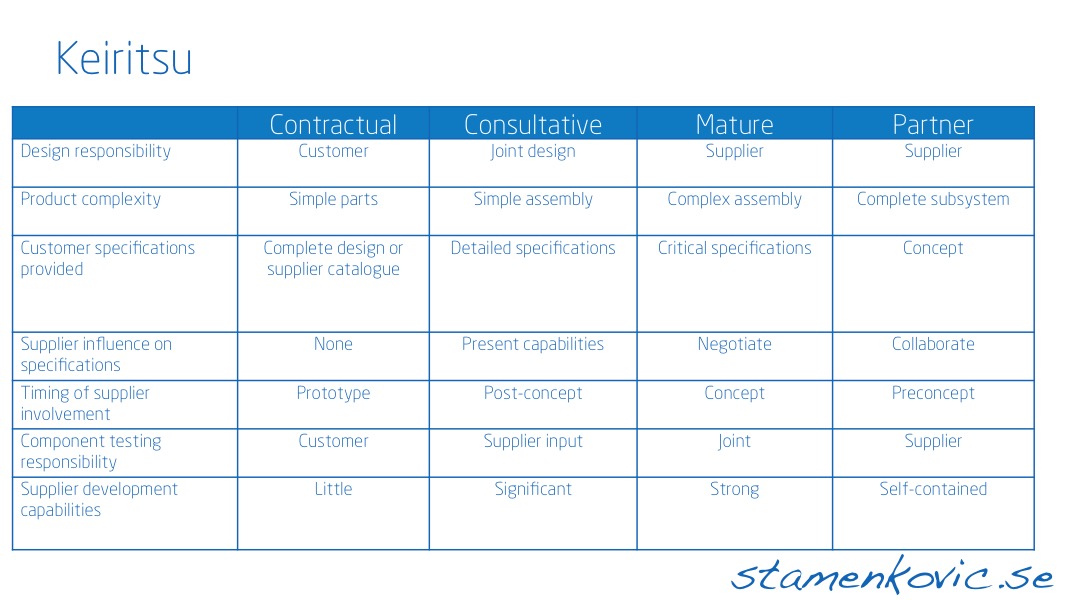

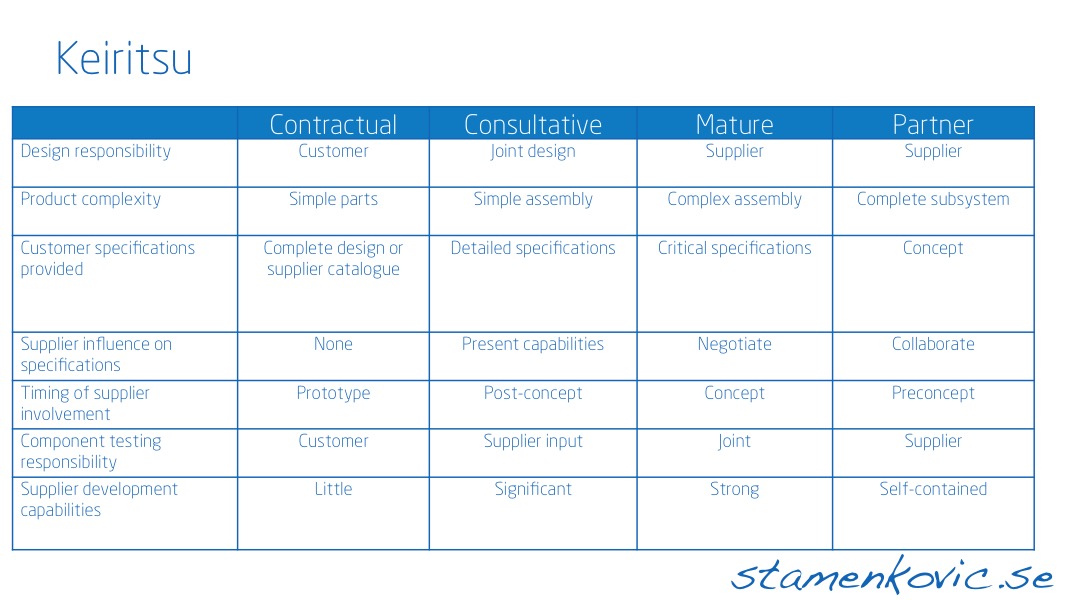

The power of the Keiretsu

Keiretsu means set of interlocking corporations. In the keiretsu model, a broad set of different types of companies cooperate in business and hold equity in each other. Under this arrangement, suppliers were told which companies they could do business with; because the affiliated automakers controlled this, they were able to trust the suppliers with sensitive information, the kind of information generally kept secret and guarded even within individual companies.

Are All Suppliers Created Equal?

Toyota uses a tier structure for its supplier, similar to a hierarchical organizational chart. It deals primarily with the first tier, the largest suppliers who provide complete subsystems directly to Toyota. To further manage the keirutsu, Japanese suppliers have four major roles for Toyota’s different vehicle programs, each of which are discussed below:

- Partner. This is the highest level, which includes companies like Denso, Araco, and Aisin. These companies have grown to be comparable in size to Toyota and are technically autonomous. They can design their own subsystems and components and have complete prototype and test capabilities. They are involved in the earliest concept stages at Toyota, and they often develop sketches before Toyota has created a contract or even developed formal specifications for the subsystem. Partners have a large number of “guest engineers” housed in Toyota’s design offices near Toyota engineers for 2- to 3-year stays. These engineers help augment Toyota’s engineering workforce without increasing Toyota’s payroll; they collaborate on the design and solve design problems. By cycling engineers through Toyota as guest engineers, suppliers are also training their workforce in the Toyota’s product development system. They are only a few suppliers that fit the image of a full partner, and even these suppliers must continually prove themselves.

- Mature. A majority of first-tier suppliers are just a half step below the partner level. They have matured to the point that they have very strong engineering and manufacturing capabilities, but they are a bit less autonomous and depend more on direction from Toyota than partners. Their products are not quite as complex, and they rely on specifications on Toyota. It is here that Toyota’s set-based approach to setting specifications differs from the approach used in U.S. auto companies. Whereas U.S. companies set detailed and rigid engineering specifications for suppliers, Toyota provides less restrictive specifications and views them as targets. When delivering these somewhat vague specifications to suppliers, Toyota often uses the word gurai, the Japanese equivalent of “about”. One of the difficulties Toyota has had working on engineering tasks with U.S. suppliers is that these suppliers need explicit instructions, including detailed specifications and tolerances before they can act. Worse yet, if Toyota does not specifically ask the supplier for something, it is not given. This has been a frustrating experience, particularly for Toyota’s Japanese engineers who are used to working with Japanese suppliers, who often anticipate their needs. Mature suppliers do not wait to be asked. They take initiative and suggest. Toyota wants the suppliers to think for themselves, challenge the requirements, and provide value-added ideas to the process.

- Consultative. These suppliers make commodities like batteries and tires, but Toyota also taps into their expertise, getting ideas for products still being decided upon. Consultative suppliers influence the specifications by recommending their own innovations, for example, a new tire with new characteristics. These products are generally not technically complex, and there is less intense engineering collaboration with this supplier group except around the prototype testing and launching stages.

- Contractual. Toyota purchases nuts and bolts, brackets, and spark plugs – parts that do not require a major partnership. In many cases, Toyota simply specifies what it wants, picking from a catalogue or engineers a special component, if needed, and then selects a supplier. First-tier suppliers have a host of these commodity suppliers, but even with these contractual suppliers, Toyota closely monitors quality, cost, and delivery. Toyota seeks out contractual suppliers that deliver just-in-time shipments, parts packaged in the right quantity and right container, and only the best quality. These suppliers are also expected to work diligently on cost reduction.

Toyota teaches the Toyota Production System to suppliers at all levels, chooses its suppliers carefully, and is cautious about which supplier it lets into its extended family and to what degree it becomes intertwined with its partners.

The Guest Engineer System

Toyota often has a crew of hundreds of engineers from suppliers, residing full time in its product development office called guest or resident engineers. This has an obvious benefit – free engineering resources for Toyota. But this is not the purpose. The purpose is integration. When Toyota invites a supplier to send guest engineers, it is a significant commitment to long-term coprosperity.

The Crux of Outsourcing Strategy

Although Toyota outsources parts and even engineering, it does not outsource competence or relinquish control. Toyota is not willing to give up internal competency, even though it may be cheaper or more convenient to do so.

Mastering Core Technology

Toyota never transfers to its supplier all of its core knowledge or full responsibility for any core are. When new technology is core to a vehicle, Toyota distinguishes itself from the rest of the pack by diligently working to master the technology and becoming the best in the world at using it. As a lean organization, Toyota is fully aware that mastering any core technology internally helps to 1) manage suppliers effectively (e.g., understand true costs), and 2) continue to learn as an organization to stay at the forefront of the technology.

One of the trends in the auto industry (as well as in many consumer-driven business) is modularity. Like other products, cars can be divided into a set of interdependent modules (interior cockpit, corner module, etc.), each of which can be sourced to an outside supplier to engineer, then built, and shipped in sequence to the assembly line. The automakers bolts together the modules and the work is done.

Toyota, preferring to keep more control internally, was especially conservative about joining this trend. Instead, Toyota created 13 or 14 keiretsu megasuppliers and, by 2003, it had developed its own unique strategy for modularity, one that gave it a degree of control and internal competency. On surface, there is an inherent contradiction in supplier relationships in the lean PD approach. On the one hand, when you do business with any outside company, you need to treat them with the respect accorded a partner. Moreover, when suppliers become part of the inner workings of your company, they then become part of the extended network that make up your enterprise. Trust and openly sharing information are critical to success. On the other hand, it is important to define your core competency properly and accurately, and then aggressively find ways to maintain it.

Treating Suppliers Respectfully and Reasonably

The bottom line in a lean PD process is that you treat suppliers respectfully and reasonably. After all, they are engineering and building critical portions of the product that you are trying to sell to the customers who you want to view the product as world-class goods. Trust between Toyota and its suppliers is a two-way street; each partner benefits because each partner is willing to go the extra mile down this street to keep the relationship strong.

In Summary:

Fully Integrate suppliers into the product development system

Customers view purchased components as a part of the product and want the whole product to be problem free. They do not care if a problem was not your fault because your supplier was not reliable. Whoever sells the final product is responsible. For this reason, suppliers of core components must have the same level of engineering and manufacturing capability to contribute quality parts as your lean enterprise has in engineering and manufacturing quality products. In addition, suppliers must be compatible. They must fit seamlessly into your product development system, your launch system, and your manufacturing system. This requires learning how to work together through repeated experiences. It is your responsibility to communicate clear expectations. To accomplish this, Toyota brings selected suppliers into the simultaneous engineering process very early in the concept stage. Suppliers make a serious contribution to simultaneous engineering, knowing that they are investing ahead of the payback that will come in the production stage. This is something to emulate.

Source: Liker, J.K and Morgan, J.M, The Toyota Product Development System: Integrating People, Process and Technology, Productivity Press, 2006